Australia wants to be Maker not a Taker in an AI-driven world

That will require a lot more than the shallow rhetoric and analog thinking we've been having for decades

“The real problem of humanity is that we have Paleolithic emotions, medieval institutions, and godlike technology.” — E.O. Wilson

In those words, Edward Osborne Wilson, the famed biologist and chronicler of human behaviour, nailed the central tension of our time. We are emotionally wired for small, tribal groups, yet we now wield technologies that can radically disrupt and reshape — or destroy — the planet.

AI, gene editing, drones, cyberwarfare, nuclear weapons: all moving faster than our institutions, politics, or public consciousness can keep up.

Wilson died in 2021 at age 92 when the Covid pandemic was still raging, but a year before OpenAI’s ChatGPT launched a global AI arms race. While the new cold war between the US and China was changing the geopolitical threat landscape, Russia hadn’t yet invaded Ukraine and Israel hadn’t been pulled into regional war.

In other words: the new world disorder hadn’t yet revealed itself the way it now has.

Which brings us to Australia — a wealthy, still stable democracy that is struggling to grasp the realities of the technologically-accelerated era we are in.

“We're in a world of only hard choices now,” said Dr John Kunkel on the Australia in the World podcast. Dr Kunkel is Senior Economic Adviser at United States Studies Centre.

“There is a brief window, I think, for communicating differently to the Australian people about the world we are in and issues around technology competition.”

The recent federal election delivered the Anthony Albanese-led Labor government a thumping majority and a second term (or more) in power. But the campaign exposed a political leadership class stuck in the past and out of its depth.

In a world where technology is power, geopolitics increasingly volatile and economic insecurity and tariff-driven coercion a daily reality, rival political party leaders couldn’t communicate those shifted realities to Australians.

Instead, we heard recycled ideas, lullaby language about not needing to copy or learn from other countries and short-term sweeteners for cost-of-living pain.

Now an emboldened Labor government says its second term will be all about delivery on first term promises – housing, bolstering Medicare, the renewables only Future Made in Australia (FMIA) agenda; getting through the cost of living and energy crises.

“We will be a nation of makers, not takers, and we’ll do it the Australian Way with no one left behind,” the Prime Minister declared during a recent National Press Club address.

It’s a new slogan for a second term, retiring the over-used “Churn and Change” catchall so often repeated by Treasurer Jim Chalmers over the past few years.

Also new on the Government’s agenda is its sudden recognition that AI could be a critical enabler – “a gamechanger” – of a yet undefined national productivity agenda.

I’ll come back to that shortly.

But the harsh reality is Australia is being left behind relative to most OECD nations and regional neighbours. The new slogan can’t mask the country’s policy, skills and industrial and defence capability gaps, nor make a complacent, government-dependent culture into an entrepreneurial and resilient one.

Meanwhile, the country’s negative momentum gains speed:

In the just released World Competitiveness Yearbook, Australia dropped five places to 18th overall and a shocking 21 places to 49th in the productivity and efficiency rankings.

Our economic and security vulnerabilities are being exposed daily. The AUKUS defence partnership is under a 30-day review by the US Trump administration and could be scrapped. A much hoped for opportunity for Prime Minister Albanese to persuade President Trump on the mutual value of Aukus at this week’s G7 confab was also ditched at the 11th hour due to the new hot war between Israel and Iran.

The country’s taxpayer subsidised Future Made in Australia (FMiA) and the green energy reindustrialisation agenda is stalled, if not broken. We are relying almost entirely on wind and solar for an industrial energy reboot that demands reliability and scale. It has resulted in sky-high energy prices and is increasingly out of step with global trends, where even longtime climate champions are rebalancing toward energy realism.

To have a chance of reversing Australia’s negative momentum requires us to drop the pretence that we can continue as we have.

With all the economic and geopolitical uncertainty, it is clear that in this and the next phase of the 21st century it is not useful to compartmentalise genuine sovereign technological capability from economic or national security.

Among rich, educated western nations, Australia has been woefully late to that realisation.

For decades, our approach to technology for business, government and defence contracts was passive: import what works, adapt it locally where needed, and avoid the hard stuff of funding, developing, commercialising and scaling our own.

But that model no longer holds. We’re now in a world where technology is power; the sharp edge of global economic competition and the foundation of national security.

It shapes trade, controls supply chains and underpins security. Economic policy is now tech policy.

And whether its nuclear submarines, drones, AI data centre infrastructure or green tech, they are all just delivery vehicles for digital tech.

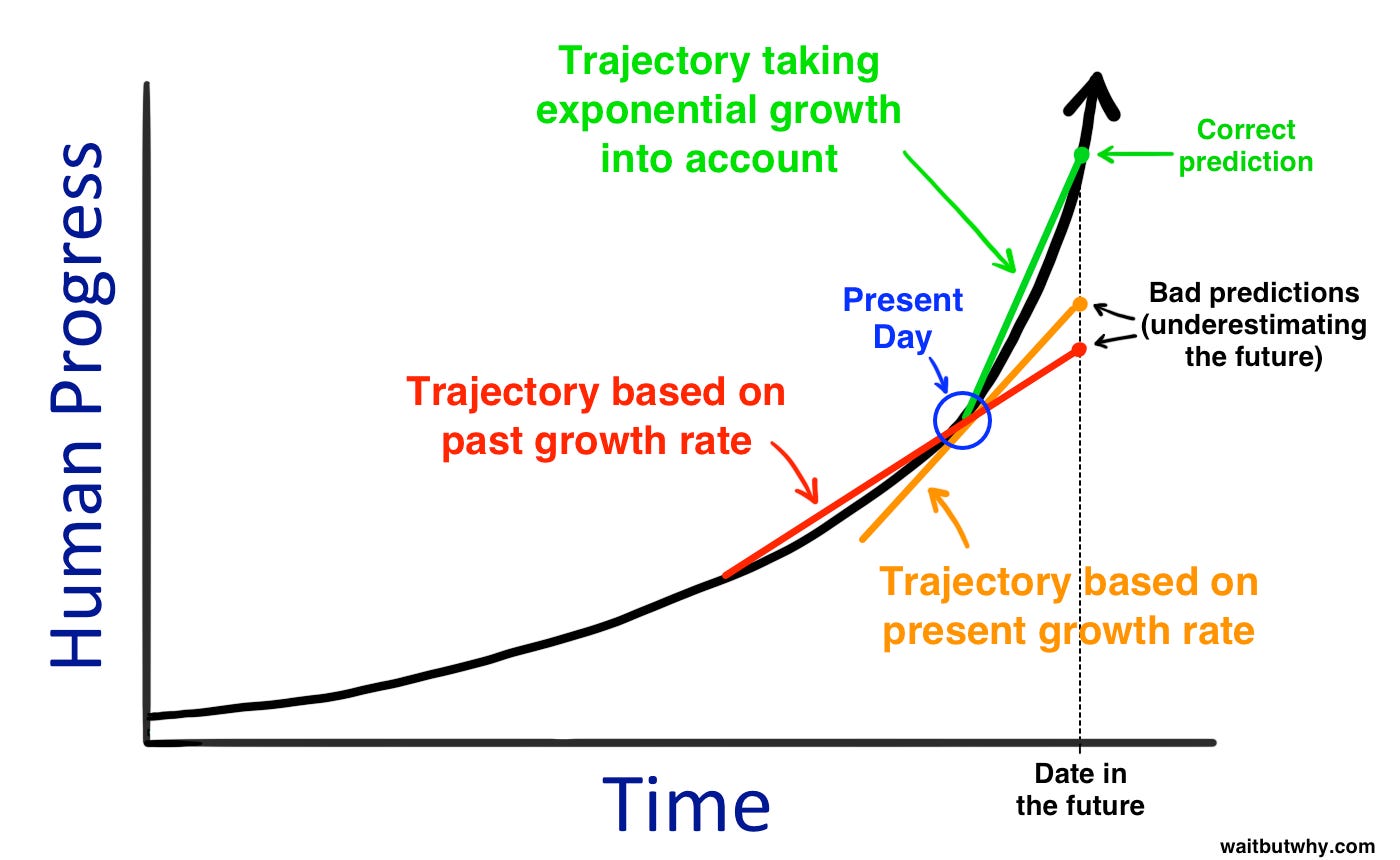

Throughout the multi-decade rise of the internet and digital data revolution, now being amped exponentially with generative AI, Australian political and business leaders have remained stubbornly analogue. That out-of-date mindset has to go, and fast.

In a notable pivot from its first term reluctance to understand and invest in the AI era, the Albanese government is now beginning to frame artificial intelligence as a key enabler of national productivity.

Industry Minister Tim Ayres recently urged Australia to “lean in” to AI, aligning the rhetoric with Labor’s broader “Future Made in Australia” agenda. We also have a new Assistant Minister for the Digital Economy, Dr Andrew Charlton, in a newly created role.

In another change of heart for Labor, Treasurer Jim Chalmers is now signalling support for light-touch AI regulation. The treasurer has also pushed back on the suggestion that the trade unions will have some sort of veto power over the pace and shape of how AI is rolled out into workplaces around the country.

The Australian Council of Trade Unions’ AI policy endorsed at the most recent ACTU Congress, mandated training and consultation for emerging technology. They have also called for a legally enshrined “right to disconnect” from AI tools and systems outside work hours.

In practice, such a rule would be almost impossible to define or enforce in an AI-integrated economy where automation, remote collaboration, and real-time data are core to competitiveness. Hardwiring this kind of rigidity risks stifling innovation, limiting flexibility, and undermining the very productivity gains Australia urgently needs to remain globally relevant.

While the change of approach to AI from defensive to offensive, at least rhetorically, is a step in the right direction, we are a long way from a coherent, forward-leaning national strategy.

To paper over this vacuum the government has announced a Productivity Summit for mid-late August.

Again, there are no further details beyond the news that just 20–25 yet unknown participants – business group leaders, the ACTU and Productivity Commission chairperson, Danielle Wood among them - who will gather in the Cabinet room in Canberra.

This is also around the same time when the Productivity Commission will release the first draft of five new inquiries focused on identifying ways to materially boost Australia’s productivity. The PC has been working on those since December.

Harnessing data and digital technology is one of the five key pillars, along with Creating a more dynamic and resilient economy; building a skilled and adaptable workforce; delivering quality care; and of course, investing in clean energy and the net zero transformation.

Privately, business and industry scepticism about the outcomes of the August Productivity Summit is already high. Business leaders still have clear and unpleasant memories of the much-criticised 2022 Jobs and Skills Summit, which was described as a "stitch up" of agreements made by the Government before anyone sat down.

Another key and valid concern, especially from within the domestic tech sector, is whether the Labor government will have the right mix of people with the right mix of expertise, ambition or urgency in the room - those technically savvy and globally ambitious new industry and market makers that have been so often ignored by political and corporate leaders.

There are also valid concerns, based on the Productivity Commission’s track record of ignoring home grown technology capability in favor of reflexing to the safety and security of the foreign tech giants, that the same approach will be adopted with AI.

The Prime Minister’s joint public announcement this week in Seattle, with Amazon Web Services Chief Executive, Matt Garman did little to allay those fears. AWS announced it will increase its investment in AI data centre infrastructure and wind and solar farms in Australia to $20 billion over 5 years.

But the announcement was extremely light on detail and was seen by many as more theatre before the Prime Minister’s then scheduled meeting on AUKUS with President Trump at the G7 meeting in Canada. The meeting was cancelled at the last minute, as President Trump left the G7 early to attend to the more pressing Israel-Iran war.

Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) itself lacks depth in science and technology leadership, much less the increased and critical role risk-based entrepreneurship, venture capital and bold ambition is playing in the AI era.

Similarly, survey after survey reveals that public awareness and quality discourse around digital economy, data and AI experimentation, implementation and new business creation remains very low in Australia, as it does in the country’s corporate boardrooms.

While the Prime Minister has described the Summit as a “call to action,” many see it as a political placeholder — a forum likely heavy on consensus and light on challenge and competitive global technological realities.

Without a radical uplift in the national imagination and political will, the summit risks becoming yet another tightly stage-managed talkfest — at a time when Australia desperately needs a bold, integrated plan for AI-era productivity.